Necropsies are the animal equivalent of an autopsy. They are performed when animals die and a definitive diagnosis is wanted. The field of veterinary medicine that performs necropsies is known as pathology. Pathology is the science of the causes and effects of diseases. Pathology can be split into two main categories: gross and histopathology. Gross pathology looks at the entire animal, organ, tissue, or body cavities to look for evidence of disease. Histopathology is microscopic evaluation of tissues and individual cells to determine disease. To fully diagnosis a disease, you need both. For example, upon gross examination, you may find a large mass believed to be cancer, but you cannot determine what type of cancer it is until you look at a section of it under the microscope. In most cases, a different veterinarian is responsible for each part of the necropsy.

It is important when performing a necropsy that each person follows the same set of steps so that nothing is missed. Please keep in mind that this is for mammals as other vertebrate groups have anatomical differences that I will discuss at the end.

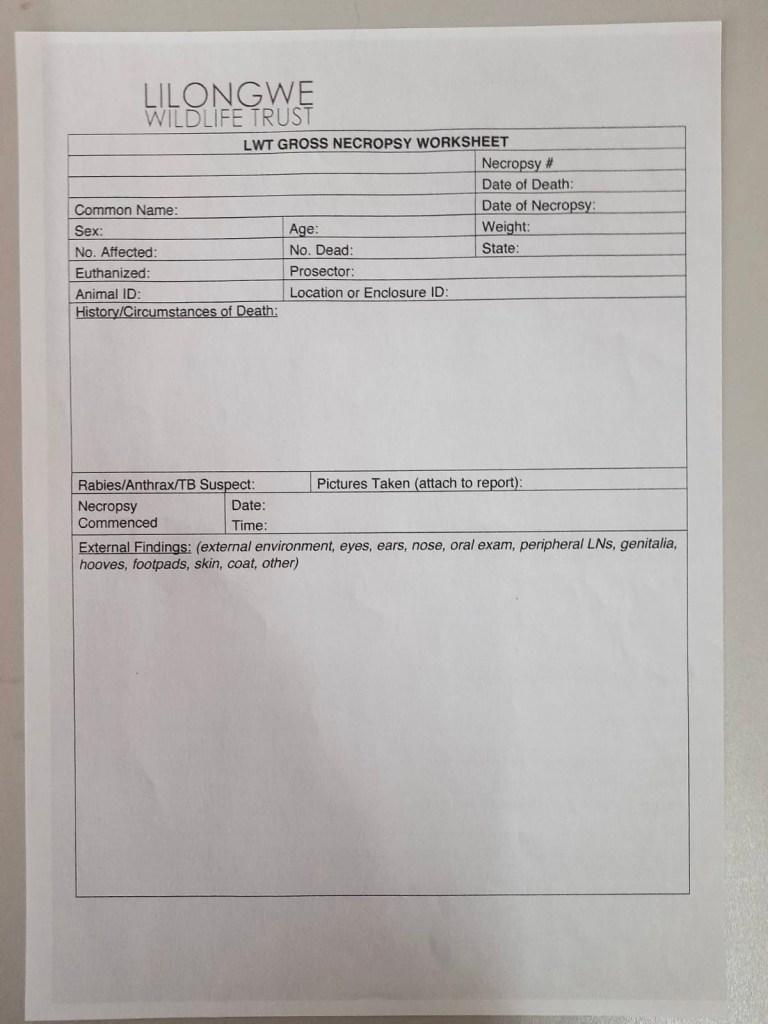

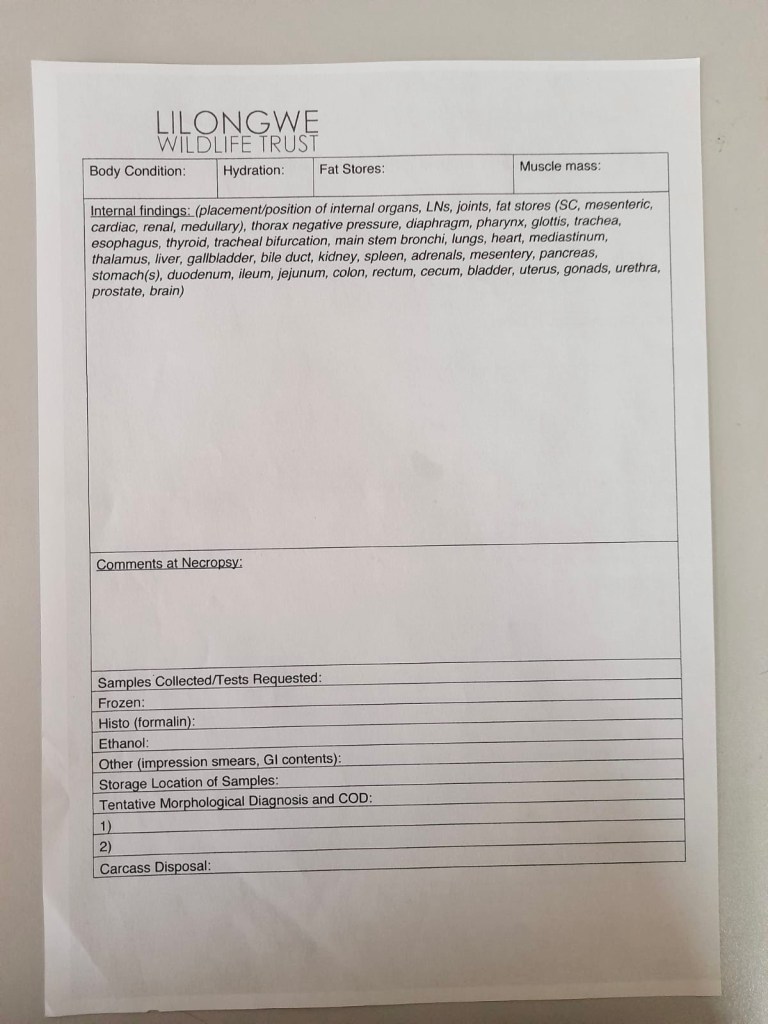

- Step 1: History

- Providing a detailed history about the animal can help to eliminate some of the possibilities of death. A history should include the animal’s species (or breed), age, where it was found, how long it had been deceased, and any other information about its life before it died.

- Step 2: External examination

- When performing a necropsy, it is easy to get caught up and want to get right into the body, but the outside can tell you a lot as well. A full physical exam should be performed before making an incision. The pathologists should exam the eyes, ears, nose, mouth (including inside), the fur, nails/feet, and body condition. Any abnormalities or injuries should be noted in the report. Certain changes are normal after an animal dies and those can be ignored.

- Step 3: Internal examination (occurs in multiple steps)

- The internal examination is the most intense part of the necropsy. Most pathologists start in the abdomen and then move into the thorax. Once an incision is made, location of the organs should be noted. Things like masses can displace organs from their normal location.

- Step 4: Removal of Gastrointestinal Tract

- The gastrointestinal tract takes up the largest portion of the abdomen so to make visualize of other organs easier, it should be removed. It is important to try not to puncture the tract while removing it – intestinal contents smell really bad! The GI tract is then placed to the side to be examined later.

- Step 5: Examination of Abdominal Organs

- Once the GI tract is removed, the urinary and reproductive tracts will be visible. Each kidney should be removed with their associated adrenal gland. The adrenal glands sit right on top of each kidney and can be difficult to identify but they are important to look at because they are responsible for the stress response. Each kidney should be cut open to observe the structures inside and the size of each should be compared. Any abnormalities will be noted on the report.

- The reproductive tract should be removed and examined next. In dogs and cats, it is common for these parts to be removed so it is important to know whether it is a fixed animal.

- Females: If the reproductive tract is present, each ovary should be cut open. The uterus can also be cut open. The uterine horns can be examined to see if there are any fetuses present.

- Males: The most important part to examine are the testes. Size and shape should be compared between the two. The prostate will sit near the bladder and can also be examined.

- Once these organs have been evaluated, we can return to the GI tract. Each organ should be identified and observed for any external issues. The organs you are looking for are liver, gallbladder (if the species has one), stomach, intestines (duodenum, jejunum, ileum), cecum (if distinct in the species), and the colon. Each of these organs should be cut open to look for abnormalities.

- Step 6: Examination of Thoracic Cavity

- The easiest way to enter the thoracic cavity is through the diaphragm. Before cutting it, it is important to check if the diaphragm was intact when the animal died. Once you are through the diaphragm, the ribs should be cut to expose the heart and lungs. Similar to the GI tract, each of these organs should be cut open and observed for pathological changes.

- Step 7: Collection of Samples

- Since the majority of the postmortem is looking for gross pathology, once all the organs have been examined samples can be collected for histopathology. These samples can be from a variety of tissues depending on what is found. Any organs with abnormalities should be sampled. Sampling involves taking a portion of the organ that is representative of the abnormalities and placing it in a container with formalin to preserve it for transport. When the samples arrive at the lab, the pathologist there will create slides to observe under the microscope. Through these observations, they can make a diagnosis for the disease processes seen.

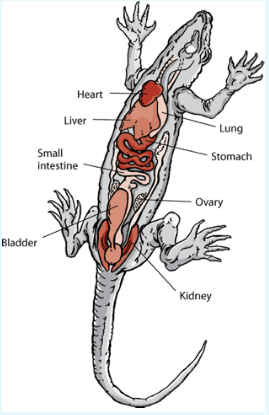

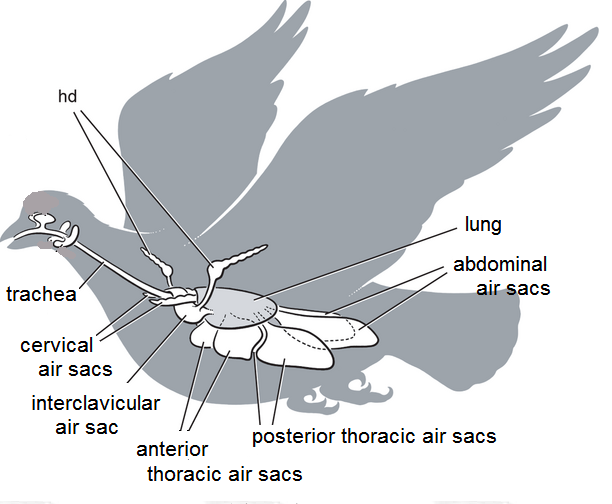

While most pathologists will perform necropsies on mammals, wildlife veterinarians will handle a wide variety of species. There are some very important anatomical differences between the different classes of animals. Some of the most important ones are explained below.

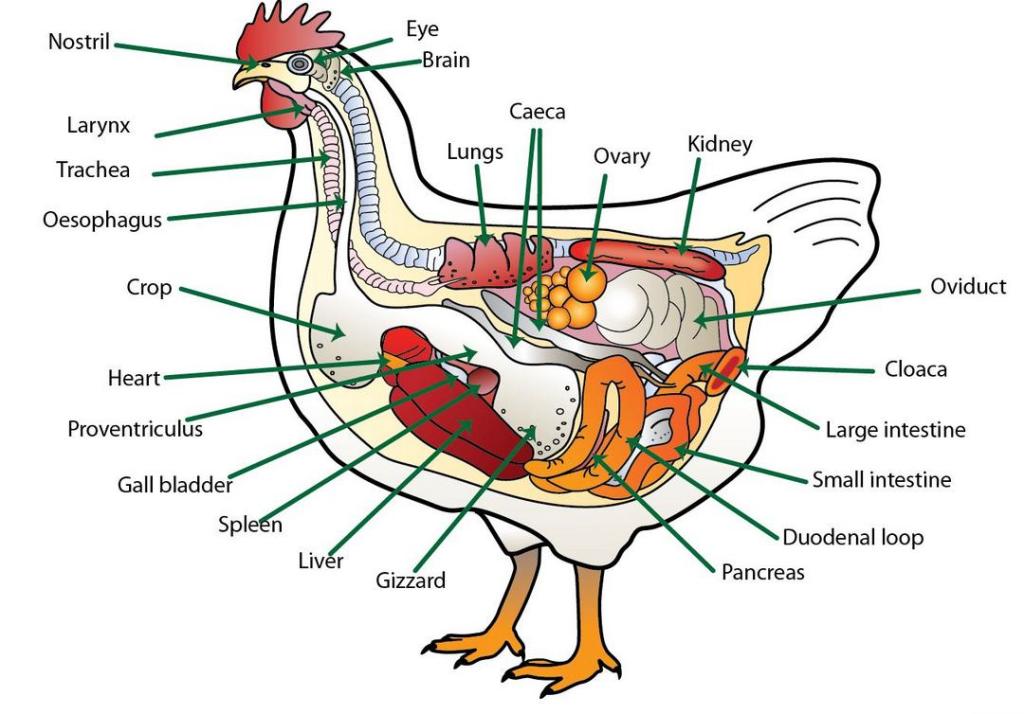

- Reptiles, amphibians, and birds do not have a diaphragm. This means that there is no separation between the abdomen and the thorax. Instead, this body cavity is called the coelom. When performing the necropsy, you still start in the “abdominal organs” but there will not be a distinct separation.

- Birds have diffuse lungs and air sacs. These aid in flight. The air sacs are in pairs (except one) along the front (ventrum) and back (dorsum). It is important to examine each air sac because certain diseases affected different sets of air sacs. The lungs are not fixed structures making it difficult to locate them, but it is important to find and examine them.

- Birds, reptiles, and amphibians have a cloaca. The cloaca is the common opening for the urinary, GI, and reproductive tracts. Mammals have unique openings for each of these systems, so it is easier to determine if disease is affecting one from an external examination. In these species, abnormalities around the cloaca can mean a huge number of diseases so internal investigation is crucial to determine which system is the culprit.

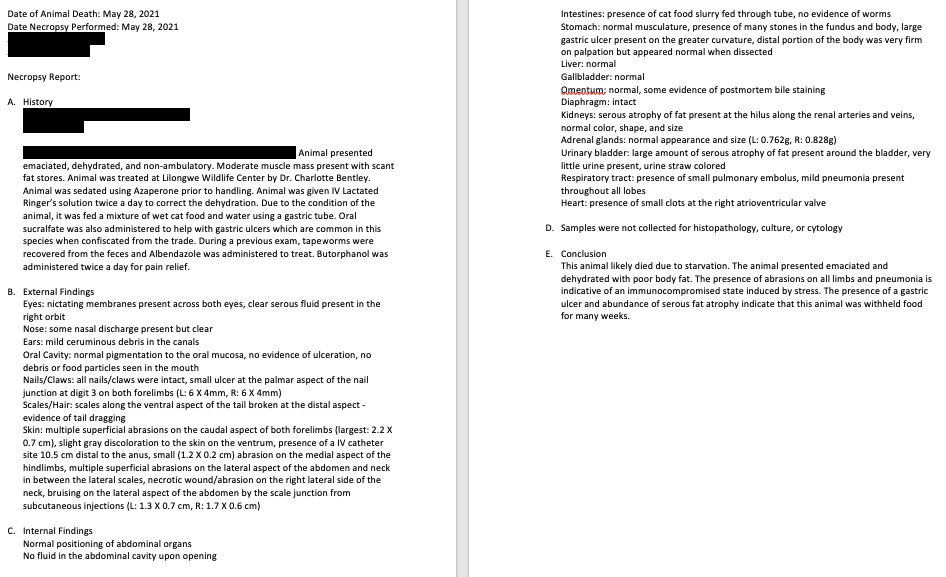

In addition to necropsies used for diagnostic purposes, they can also be used in forensic cases where animals are involved. In cases of abuse, neglect or illegal possession of an animal, a necropsy may be performed to determine if the cause of death was related to the abuse or neglect so those findings can be used as evidence. There are specific courses in the US that must be completed by veterinarians to certify them as Forensic Pathologists. These pathologists are qualified to write official court reports and testify. This is a common practice here in Malawi for certain species that are involved in the illegal wildlife trade. I spoke with Laston, a final year vet student at the veterinary school in Malawi who works at Lilongwe Wildlife Center, about his experiences appearing and testifying in these cases. He is the representative for the center because he speaks Chichewa and is a native Malawian. My interview with him is below.

Me: What are common questions that you are asked related to the case?

Laston: Every question is aimed to disqualifying you as a witness. They will check thoroughly if you are qualified to testify and how much experience you have with similar cases. You have to be careful when answering the questions that you are being honest and professional but not allowing them to disqualify your findings. If the animal came to the center alive, they may try to ask whether the animal died because of intervention decisions made by the center. You have to explain why you made the medical decisions that you did and why they are not the cause of death. They also will ask if we had court approval to provide medical treatments or if those decisions were our own.

Me: What information is the most important from the necropsy? What information will you present to the court as evidence?

Laston: The most important information includes the following but is not limited to:

- Health condition of the animal when it was received from the police or the Department of National Parks and Wildlife. This includes the body condition, mentation, hydration status, and age/sex of the animal.

- If the animal was alive when it came in, the initial findings of the physical exam and what intervention was taken immediately are very important.

- All postmortem findings are important, but they should be presented in layman’s terms since most of the court personnel do not have a medical background. They encourage us to use photos as well to show the findings.

- The differential diagnosis is essential to the case. This is what you believe is the true cause of death based on all your findings.

- It is important to explain the connection between the issues found during postmortem and the welfare concerns. You also must explain how both can lead to the death of the animal. The welfare charge is the easier conviction, so we try to focus on this.

Me: How do you feel while you are on the stand giving your testimony?

Laston: To be honest, I get very nervous testifying in court. I am especially nervous if there is a defendant present.

The major differences between necropsies in Malawi and the US is the access to resources (I hope you have noticed this is a common theme!). In the US, we can easily collect samples, send them off to a lab, and have results in a few days. In Malawi, there are no labs dedicated to animal samples, so it isn’t always reliable to have samples read at a human facility. In addition, these tests are expensive even in the US so the center must be selective in deciding which cases to send samples for. For domestic animals, people in the US are generally more interested in what killed their animal and have the means to pay for a necropsy. For Malawians, animals are not seen as pets in the same way. Livestock is important for their livelihood, but most people do not have access to a veterinarian that could perform a necropsy or funds. When it comes to wildlife, the US is concerned with performing necropsies to determine if there is an outbreak of an infectious disease and our wildlife populations are well monitored. In Malawi, wildlife doesn’t have the same funding, so most cases go unnoticed. In places like the center, necropsies are performed whenever an animal dies, but histopathology is almost never included because the diagnosis found during gross examination is usually sufficient. In the forensic cases that will be sent to court, samples may be sent off if the gross examinations are inconclusive. Overall, necropsies can provide vital information for health and disease in populations and individual animals.

Medical Terminology Dictionary

- Postmortem: after death

- Antemortem: before death

- Lesion: a pathologic change

- Signalment: the breed/species, age, and sex of an animal

- Definitive Diagnosis: a disease process that can be attributed to all the pathology found ante- or postmortem

- Body condition: the overall physical condition of the animal based on muscle mass and fat content

- In dogs, we use a scale of 1-9 and in cats, we use a scale of 1-5. For our wildlife species, we typically use the 1-5 scale.

- A score of 1 is indicative of emaciation and a score of 5 or 9 is extremely obese.

- In dogs, we use a scale of 1-9 and in cats, we use a scale of 1-5. For our wildlife species, we typically use the 1-5 scale.

- Mentation: the mental state of the animal

- This is species dependent, but no animal should just lay there unresponsive

- Dorsal/dorsum: towards or on the back

- Ventral/ventrum: towards or on the abdomen

Leave a comment