Parasites are never a fun topic to discuss. They are creepy crawlers that make your skin itch and your stomach ache. Our domestic animals and wildlife deal with the same issues when it comes to parasites. We, as a society and industry, have worked hard to eliminate or reduce the number of parasites that we see in our animals.

There are two main types of parasites: external parasites and internal parasites.

- External parasites are usually invertebrates that live on the surface of the skin, maybe burrow into the skin a little bit, and cause the animal to be itchy. Most people are familiar with these parasites because they are easily seen. Most of our animals, pets and livestock, are treated for them on a regular basis.

- Fleas and mites usually just cause discomfort to the animal. If the animal is immunocompromised, fleas may overload the animal and cause more severe disease or symptoms. Mites are species-specific meaning that each animal species has a unique species of mite that infects it. Mites, in adult animals, are usually a sign that the animal is sick and unable to fight off the mites. Mites are commonly seen in puppies and kittens because of their naïve immune system.

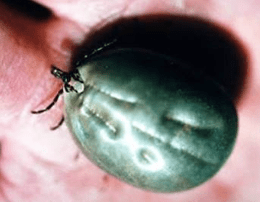

- Ticks are a much bigger concern due to the number of infectious diseases that they can carry. The most common diseases carried by ticks are Lyme disease, Babesia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, and Rickettsia. Each of these diseases is carried by a certain species of tick and has multiple forms present in different tick species. The specificity of a disease to a tick species makes these diseases very widespread. Ticks are a huge problem in livestock because people do not interact with their livestock daily, so ticks are not picked up regularly or quickly. The longer a tick stays attached to an animal, the more likely it is to spread disease to that animal. Livestock are susceptible to the same tick-borne diseases as dogs, cats, and people. The problem is far reaching in livestock because they serve as a food source. If an animal becomes infected with a tick-borne disease, they will likely become sick, not eat as much, lose weight, and decrease production for that farmer. They also might die quickly and unexpectedly causing loss to the farmer. The effect of these diseases on people who eat infected animals is not widely understood, so it is a risk to process them as a food source.

- There are several species of flies that can cause disease and decreased production. Certain species of flies lay their eggs on animal skin which can lead to issues like wolf worms or bot fly larvae. In wounds, flies can lay eggs which hatch into maggots that can increase the severity of the wound.

- Internal parasites encompass a huge variety of organisms that can infect an animal. To maintain brevity, I will only cover the most common ones seen in domestic species which can cross into wildlife. Similar to external parasites, these internal parasites can infect a wide range of host species.

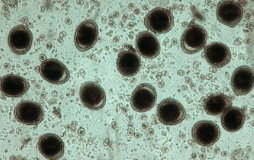

- Nematodes are intestinal worms that infect a wide range of species. These are probably the most seen parasites in our dogs and cats and ones that you would regularly deworm for. Hookworms, whipworms, and roundworms (known as the “Holy Trinity”) are the three types that we see in all our species. There are many different species of each, and they infect a different range of species. Symptoms of intestinal parasites can vary but almost all will cause diarrhea in some way. Hookworms are usually species specific. However, humans can get a form of hookworm from their animals. These worms typically stay under the skin and cause itching and discomfort in the area. Whipworms are species specific so the ones that an animal gets cannot be transferred to people. Humans have their own species which is typically only seen in children. Roundworms can be zoonotic and pose a threat to human health beyond intestinal upset. These worms migrate through the body and can cause damage to other organs as they move.

Roundworm (Toxocara canis) egg from a dog (https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/gastrointestinal-parasites-of-small-animals/roundworms-in-small-animals?query=roundworm)

- Trematodes are flatworms or flukes. These parasites require a snail or fish intermediate to develop. Once inside the body, they infect the liver and lungs but can be found in a range of organs as well. While people can be infected with animal flukes, these are very uncommon in the US. The most common way that people would get it in the US is from eating raw, infected fish. For people in Malawi, it is more common due to the lack of widespread, clean drinking water and it is more likely that they would ingest one of these snails.

- Protozoa are single-celled organisms, not visible to the naked eye that can be parasitic to people and animals. The two most common types of protozoal infections that we see in our animals are Giardia and Coccidia. These conditions are very common throughout all species and can cause diarrhea and weight loss. It is rare that humans would become infected from their animals because it is usually different species for each host. These parasites require specialized tests to determine if they are present because they are so small. They also require specific treatment besides the routine dewormers that we typically use.

In the US, it is extremely common to deworm our animals. If you have ever had a puppy or kitten, they will be dewormed at their first vet visits because of the ubiquity of these parasites. Livestock and horses are dewormed on a schedule throughout the year because they have a much higher exposure rate. Many of these parasitic eggs live in the soil or in water sourced. Livestock and horses are grazers and drink from these water sources, so they are constantly exposed. While these deworming methods have improved the health of some animals, we have created resistance within the parasites. Our traditional methods don’t always work anymore so we are constantly having to improve and change our methods of attack. However, this is a foreign concept here in Malawi. Most farmers do not have access to drugs to treat parasites, so they aren’t exposing them to it as often. House cats are almost nonexistent, and dogs are not pets like we would think in the US. Resistance still exists but not at the levels we see in the US. For this reason, our traditional methods and drugs for deworming are still very effective here.

Parasite tests are a common diagnostic tool used in all fields of veterinary field. There are many different types including fecal floats, McMaster egg counts, Baermann’s tests, and ELISA tests. Each of these tests are best for certain parasites. The fecal float is the most widely used in small animal hospitals and wildlife.

Steps for a Passive Fecal Float:

- Collect a sample

The fresher the sample, the better. Parasite eggs will break down after time outside of the body, so it is important to analyze as fresh of a sample as possible. Freezing or refrigerating a sample can preserve the eggs until examination can be done but it should be a fresh sample. It is unlikely that if you went into your backyard and collected a sample from who knows when that that sample would be diagnostic.

- Measure your fecal sample

It is recommended to use 3-5g of feces to run your test. Any amount less than this is not necessarily representative of what is occurring in the GI tract. The traditional method was to collect a sample using a fecal loop (photo below) to collect directly from a patient, but these almost never retrieve a large enough sample and commonly miss diagnoses.

- Mix your sample with float solution

There are many kinds of fecal float solution. Each one has a different specific gravity that will cause different sized eggs to float. In the US, some veterinary hospitals may have access to all these solutions and can pick and choose which one to use based on the parasite they most suspect. In smaller practices and here in Malawi, a sugar or salt solution is typically used. At the correct dilution, this solution will float all of the nematodes, some trematodes, and certain life stages of the protozoa. As you are mixing, you are trying to break up the feces as much as possible to release the eggs into solution.

- Strain your sample

Once the sample is mixed, it should be strained into a test tube. The parasite eggs are small enough to go through the strainer, but fecal pieces should not be. The test tube should be filled to the very top so that a meniscus forms (a bulging of liquid above the top of the test tube; see photo).

- Cover the test tube

Once the meniscus is present, a cover slip should be placed on top of the test tube. This cover slip is what will catch all the eggs.

- Wait 10-20 minutes

The eggs can take a little bit of time to float to the top. The longer you wait, the more eggs will reach the top and stick to the cover slip.

- Place the cover slip on a microscope slide

Cover slips are designed to sit on a microscope slide for observation. The eggs will be stuck to the cover slip and then trapped on the microscope slide.

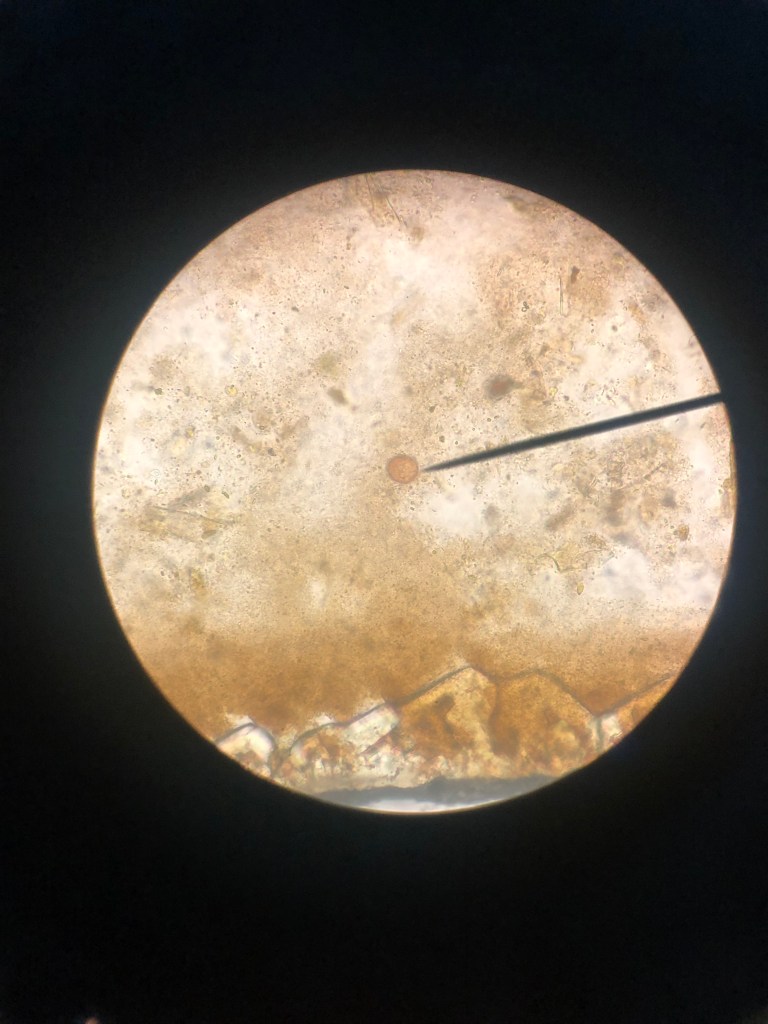

- Observe under the microscope

Anytime you are looking at something under a microscope, you should start at the lowest magnification and work your way up. Nematode and trematode eggs will be present and identifiable at 40X. Since protozoa are single-celled, 100X is required to accurately identify them. It is important not to spend too much time on this stage. The recommendation is 5 minutes scanning the entire cover slip at each magnification.

- Treat for what is found

As with all skills, it takes time to train your eyes to see the eggs, especially protozoa. The first few times you look at a fecal float, you may not see anything because you aren’t trained for what to look for. Once you identify an egg though, you will be able to find it most other times. It isn’t a perfect science but in animals showing symptoms, it works well to diagnose the culprit.

Lilongwe Wildlife Center and facilities like the LSPCA (Lilongwe Society for the Protection and Care of Animals) use fecal floats all the time. Each of the animals that undergoes a quarantine exam or an annual health check at the center will also have a fecal done. Most animals at the center will be asymptomatic unless they have a high burden because wildlife is constantly exposed to these parasites, so they are more resilient. The LSPCA is a large animal shelter in Lilongwe and a low-cost veterinarian for people in the city who have dogs as pets. This test is commonly done of the animals that come into the shelter because of the high prevalence in puppies and in the environment.

Unfortunately for us and our animals, parasites are something that will always exist in our environment. Our goal is to limit the symptoms and disease acquired from them while understanding that we will not be able to eliminate them. We also must be aware of the constant threat of resistance to our drugs and be cognizant that protocols will need to adapt to the parasites as they adapt.

Medical Terminology Dictionary

- Parasite: an organism that lives in or on another organism and by doing so causes detriment to that animal

- Host: the organism that a parasite lives in or on

- Species-specific: in reference to parasites, a parasite that only infects a single host species

- Cutaneous larval migrans: the form of animal hookworm sometimes seen in humans

- Anthelminthics: drugs that are designed to kill nematodes and trematodes

- Ectoparasite: external parasites

- Endoparasite: internal parasites

- Zoonotic: a disease, parasite, or condition that can be spread from animals to humans

- Reverse zoonosis: a disease, parasite, or condition that can be spread from humans to animals

- Ex. COVID-19 from humans to cats and Tuberculosis from humans to non-human primates

- Reverse zoonosis: a disease, parasite, or condition that can be spread from humans to animals

Leave a comment